The Story of the Hymns and Tunes

rt-song was simplified, and Johan Walther compiled a hymnal of religious songs in the vernacular for from four to six voices. The reign of rhythmic hymn music soon extended through Europe.

Necessarily–except in ultra-conservative localities like Scotland–the exclusive use of the Psalms (metrical or unmetrical) gave way to religious lyrics inspired by occasion. Clement Marot and Theodore Beza wrote hymns to the music of various composers, and Caesar Malan composed both hymns and their melodies. By the beginning of the 18th century the triumph of the hymn-tune and the hymnal for lay voices was established for all time.

* * * * *

In the following pages no pretence is made of selecting all the best and most-used hymns, but the purpose has been to notice as many as possible of the standard pieces–and a few others which seem to add or re-shape a useful thought or introduce a new strain.

To present each hymn with its tune appeared the natural and most satisfactory way

Indian Story and Song

te;-shka Society, where the dancer, with body bent and with short rhythmic steps, had kept time to the dramatic laugh of the song,–a song that had seemed so aimless to me only the night before.

“Every song of the Society has its story which is the record of some deed or achievement of its members,” said another old man who was lying beside the fire. “I will tell you one that was known to our great-great-grandfathers,” and rising upon his elbow he began:–

THE STORY AND SONG OF ISH´-I-BUZ-ZHI.

“Long ago there lived an old Omaha Indian couple who had an only child, a son named Ish´-i-buz-zhi. From his birth he was peculiar. He did not play like the other children; and, as he grew older, he kept away from the boys of his own age, refusing to join in their sports or to hunt with them for small game. He was silent and reserved with every one but his mother and her friends. With them he chatted and was quite at ease. So queer a little boy could not escape ridicule.

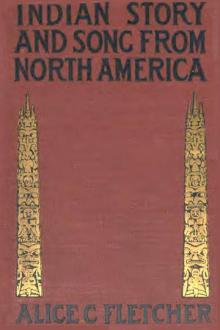

The Good Old Songs We Used to Sing, ’61 to ’65

rainard’s Sons, owners of the copyright.)

KEY OF A FLAT.

[Illustration: 18TH CORPS.]

Heavily falls the rain,

Wild are the breezes tonight;

But ‘neath the roof the hours as they fly

Are happy, and calm, and bright.

Gathering round our firesides,

Tho’ it be summer time,

We sit and talk of brothers abroad,

Forgetting the midnight chime.

CHORUS.

Brave boys are they!

Gone at their country’s call;

And yet, and yet we cannot forget

That many brave boys must fall.

[Illustration: MINIE BALL.]

Under the homestead roof,

Nestled so cozy and warm,

While soldiers sleep with little or naught

To shelter them from the storm.

Resting on grassy couches,

Pillow’d on hillocks damp,

Of martial fare how little we know

Till brothers are in camp.–CHORUS.

Thinking no less of them,

Loving our country the more,

We sent them forth to fight for the flag

Their fathers bef

How the Piano Came to Be

ecause it had too few strings, only ten to fourteen, while at the time of his writing it had sixteen to twenty-six. He makes the statement that he never spent more than a shilling a quarter for strings. The care of a lute he describes quaintly:

“And that you may know how to shelter your lute in the worst of ill weathers (which is moist) you shall do well, ever when you lay it by in the day time, to put It into a Bed that is constantly used, between the Rug and Blanket, but never between the Sheets, because, they may be moist. This is the most absolute and best place to keep It in always, by which doing, you will find many Great Conveniences. Therefore, a Bed will secure from all these inconveniences and keep your Glew as Hard as Glass and all safe and sure; only to be excepted, that no Person be so inconsiderate as to Tumble down upon the Bed whilst the lute is there, for I have known several Good lutes spoiled with such a Trick.”

Again we are indebted to Italy for the invention and name of the

A Popular History of the Art of Music

ded over all the higher operations of the mind and imagination. Thus the name “music,” when applied to an art, contains a suggestion of an inspiration, a something derived from a special inner light, or from a higher source outside the composer, as all true imagination seems to be to those who exercise it.

2. Music has to do with tones, sounds selected on account of their musical quality and relations. These tones, again, before becoming music in the artistic sense, must be so joined together, set in order, controlled by the human imagination, that they express sentiment. Every manifestation of musical art has in it these two elements: The fit selection of tones; and, second, the use of them for expressing sentiment and feeling . Hence the practical art of music, like every other fine art, has in it two elements, an outer , or technical, where trained intelligence rules, and teaching and study are the principal means of progress; and an inner , the imagination

Christian Hymns of the First Three Centuries

ea, who “speak with tongues and magnify God” ( Acts 10:45-46 ), or the Ephesians who “spake with tongues, and prophesied” ( Acts 19:6 ), or perhaps the disciples on the Day of Pentecost ( Acts 2:4 ). Irenaeus, a second century father of the Church and bishop of Lyons, referring to the scene at Pentecost, mentions the singing of a hymn on that occasion.[17] The nature of improvisations is fugitive. They arise from individual inspiration and, even if expressed in familiar phrases, are not remembered or recorded by the singer or hearer. To whatever degree improvisation played a part in early Christian hymnody, to that same degree we lack corresponding literary survivals. Possibly this is one explanation of the dearth of sources which we now deplore.

On the whole, the hymnic evidence found in the New Testament points to a predominant Hebrew influence. Both in the use of psalms and other Old Testament hymns and in the phraseology of new hymns, the Christians found themselves more at hom

The Anti-Slavery Harp

, God speed, &c.

Cold and bleak are our mountains and chilling our winds,

But warm as the soft southern gales

Be the hands and the hearts which the hunted one finds,

‘Mong our hills and our own winter vales.

O, God speed, &c.

Then list to the ‘plaint of the heart-broken thrall,

Ye blood-hounds, go back to your lair;

May a free northern soil soon give freedom to all ,

Who shall breathe in its pure mountain air.

O, God speed, &c.

THE SWEETS OF LIBERTY.

AIR–Is there a heart, &c.

Is there a man that never sighed

To set the prisoner free?

Is there a man that never prized

The sweets of liberty?

Then let him, let him breathe unseen,

Or in a dungeon live;

Nor never, never know the sweets

That liberty can give.

Is there a heart so cold in man,

Can galling fetters crave?

Is there a wretch so truly low,

Can stoop to be a slave?

O, let him, then, in chains be bound,

In chains and bondage live;

Nor never, never know the sweets

That liberty can give.

Is there a breast so chilled in life,

Can nurse the coward’s sigh?

Is there a creature so debased,

Would not for freedom die?

O, let him then be doomed to crawl

Where only reptiles live;

Nor never, never know the sweets

That liberty can give.

YE SPIRITS OF THE FREE.

AIR–My Faith looks up to thee.

Ye spirits of the free,

Can ye forever see

Your brother man

A yoked and scourged slave,

Chains dragging to his grave,

And raise no hand to save?

Say if you can.

In pride and pomp to roll,

Shall tyrants from the soul

God’s image tear,

And call the wreck their own,–

While, from the eternal throne,

They shut the stifled groan

And bitter prayer?

Shall he a slave be bound,

Whom God hath doubly crowned

Creation’s lord?

Shall men of Christian name,

Withou

Kashmir

Songs Out of Doors

ate replying,

Shaking the tune from his wings

While he is flying:

_Surely, surely, surely,

Life is dear

Even here.

Blue above,

You to love,

Purely, purely, purely._

There’s wild azalea on the hill, and iris down the dell,

And just one spray of lilac still abloom beside the well;

The columbine adorns the rocks, the laurel buds grow pink,

Along the stream white arums gleam, and violets bend to drink.

This is the song of the Yellow-throat,

Fluttering gaily beside you;

Hear how each voluble note

Offers to guide you:

_Which way, sir?

I say, sir,

Let me teach you,

I beseech you!

Are you wishing

Jolly fishing?

This way, sir!

I’ll teach you._

Then come, my friend, forget your foes and leave your fears behind, And wander forth to try your luck, with cheerful, quiet mind; For be your fortune great or small, you take what God will give, And all th

The Modern Scottish Minstrel, Volume IV

bted; but the rise of Burns hastened the result, as being itself a main element in propelling civilisation and diffusing genuine taste. His dazzling success, too, excited emulation in the breasts of our men of genius, as well as tended to exalt in their eyes a country which had produced such a stalwart and gifted son. We may, indeed, apply to the feeling of pride which animates Scotchmen, and particularly Scotchmen in other lands, at the thought of Burns being their countryman, the famous lines of Dryden–

“Men met each other with erected look,

The steps were higher that they took;

Each to congratulate his friends made haste,

And long inveterate foes saluted as they pass’d.”

The poor man, says Wilson, as he speaks of Burns, always holds up his head and regards you with an elated look. Scotland has become more venerable, more beautiful, more glorious in the eyes of her children, and a fitter theme for poetry, since the feet of Burns rested on her fields, and since his ardent eyes glow